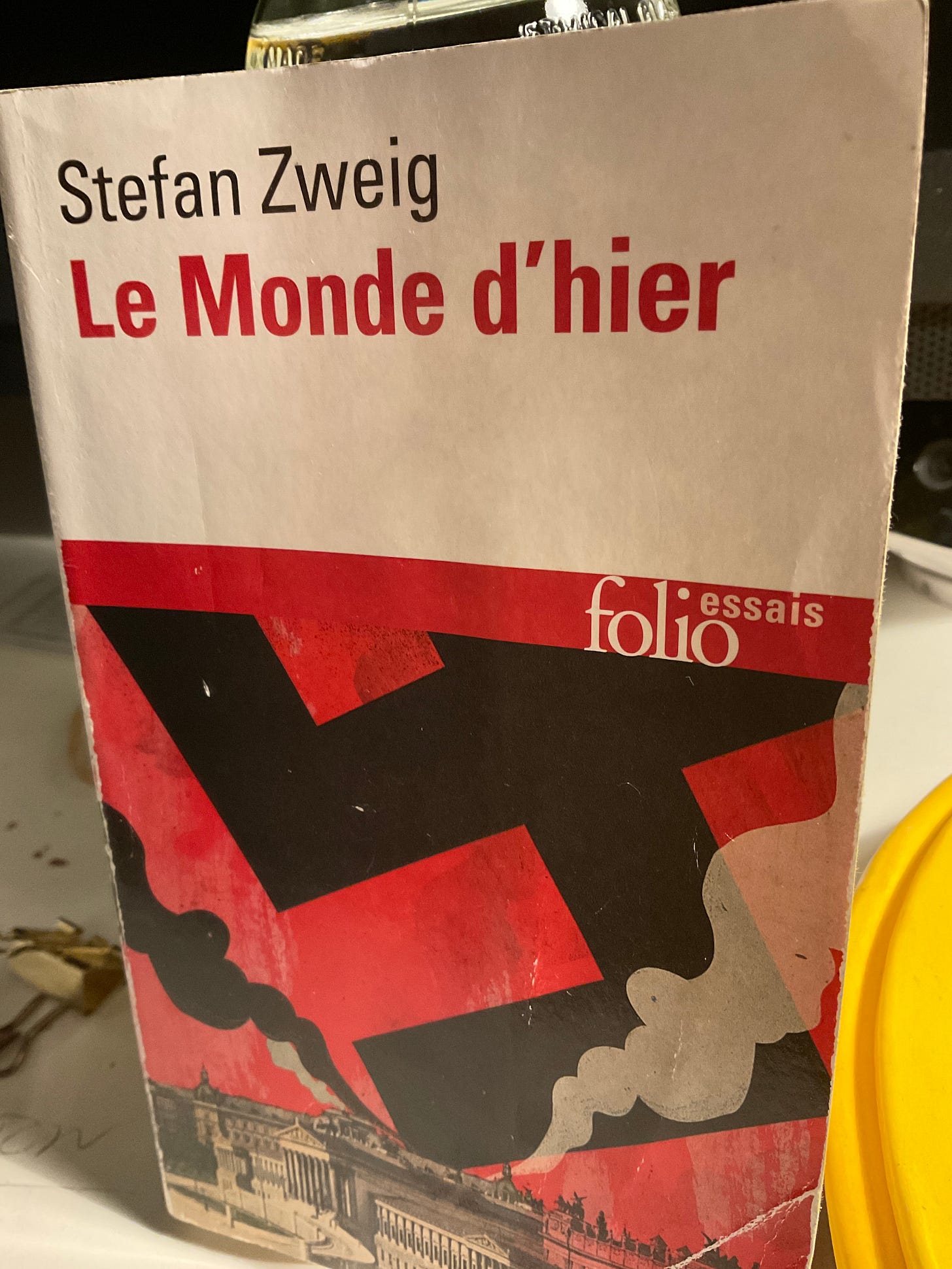

When my sister urged me to read The World of Yesterday, Stefan Zweig’s 1941 memoir, I expected a wistful ode to a lost era. Instead, I found a chilling prophecy. Zweig, a Jewish writer who fled Nazi Europe, wrote not just to mourn his vanished world, but to sound an alarm about the forces that destroyed it: nationalism’s venom, democracy’s fragility, and humanity’s capacity to normalize cruelty. Today, as I turned the pages, his words felt less like history and more like a warning written in blood for our time.

The parallels are haunting. Zweig watched as 1930s Europe succumbed to strongmen who weaponized fear, scapegoated minorities, and promised greatness through division. He saw crowds cheer as truth was replaced by slogans, intellectuals dismissed as traitors, and neighbors turned against neighbors. Now, almost 100 years later, the same shadows loom. Demagogues vilify refugees and immigrants as “invaders,” dismiss facts as “fake news,” and frame compromise as weakness. From the rise of far-right movements in Europe to the erosion of voting rights and reproductive freedoms in America, the playbook of authoritarianism feels eerily familiar.

Zweig’s greatest horror was how swiftly decency unraveled. He recalled a time when Vienna’s cafes buzzed with debates about art and progress—a world that “believed in the straight line of ‘progress’ onward and upward.” But that faith shattered as fascism spread, not with a sudden explosion, but through incremental lies: the dehumanizing jokes, the casual acceptance of injustice, the quiet belief that “order” mattered more than freedom. Today, we see similar cracks. Conspiracy theories metastasize online, journalists are branded “enemies of the people,” and marginalized communities face escalating violence. As Zweig warned, “Every act of tolerance is seen as weakness, every act of mercy as a betrayal.”

Yet what struck me most was his reflection on apathy. Zweig’s generation, he wrote, failed to grasp the danger until it was too late. They dismissed Hitler as a clown, trusted institutions to hold, and clung to the naive hope that extremism would “burn itself out.” Sound familiar? Today, too many shrug at rising authoritarianism, believing democracy too robust to fail or crises too distant to matter. But Zweig’s life—a stateless exile who died by suicide in 1942, despairing of humanity’s future—reminds us that complacency is complicity.

When I closed The World of Yesterday, my sister asked what I’d learned. “Zweig’s world didn’t end because evil triumphed,” I said. “It ended because too many good people convinced themselves it couldn’t.” Let’s hope we are not going to make the same mistake.